“I’ll never forget that phone call when the social worker told me they had found us a child. My husband Barry was not at home that night. He was at an Upward Basketball game, coaching other people’s children, teaching them to love sports and to play with integrity, when I got the call. The social worker said she had sent an email with a picture, but I didn’t need to read the email or see the picture. I knew I wanted her, whoever she was, and didn’t think twice about saying yes. That sounds odd to some people, but let’s face it, no mother gets to see her child before she decides whether she wants her. When God gives you a child, you want her, no matter what.”

Michelle Burney, vice president of Holmes Community College Grenada Campus, recounts the arduous, yet rewarding process of adopting a child from a third-world country and the remarkable timing of how everything came together.

“Since I was young, I knew that I wanted to adopt a child. I can still point to the spot in my yearbook where I wrote down that in however many years, I would adopt a child.”

Twenty years later, after unsuccessful attempts at having a child, Michelle and Barry were drawn immediately to Bethany Christian Services, the adoption agency her sister and her husband had used to adopt their daughter from China. Bethany Christian Services has offices in 20 countries around the world, including Guatemala—one of the easiest countries to adopt children from at the time.

“We didn’t want to adopt domestically, not because the children here in the United States are not in need of parents, but because we were told that the adoption process would be easier if we adopted a child from Guatemala and I loved the Hispanic culture and people. No one knew, however, that just as we started the process, UNICEF would begin to start tightening restrictions on adoptions from Guatemala.”

Along with the increase in the number of adoptions from Guatemala, profit for attorneys and agencies had grown into the millions, which had invited exploitation and unethical behavior by some private entities. The new restrictions were intended to protect Guatemalan children and families, but, at the same time, they made it harder for well-meaning families to adopt children who were often living in poverty. Everything became a time crunch for the Burney family to secure a child. What was supposed to take three months in a seamlessly easy process, ended up taking over a year as Michelle and Barry waited to hold their soon-to-be daughter.

“Every country has its own adoption laws. For the most part, you pick an adoption agency first, and then, with their help, you choose a country from which to adopt. Next, you complete a dossier or list of our preferences for your adopted child. This may seem easy, but hundreds of forms that must be translated into the other country’s, Spanish in our case, come with each step; and because the birth mother couldn’t afford to keep her daughter, we had to pay all of the expenses. Barry and I jumped through crazy hoops and more crazy hoops in the jungle of bureaucracies.”

While the Burney family was going through a mountain of paperwork, the birth mother also had to complete task after task, as they traversed through the various Guatemalan agencies, taking pictures with the child at the beginning and end of the adoption process and taking a DNA test at the beginning and end of the process.

“The requirements imposed on the birth mother make it particularly hard to adopt a child because the mother has to relive and think about her choices not only at the beginning of the process, but also at the end. This is the point where most people end up losing their potential adopted child.”

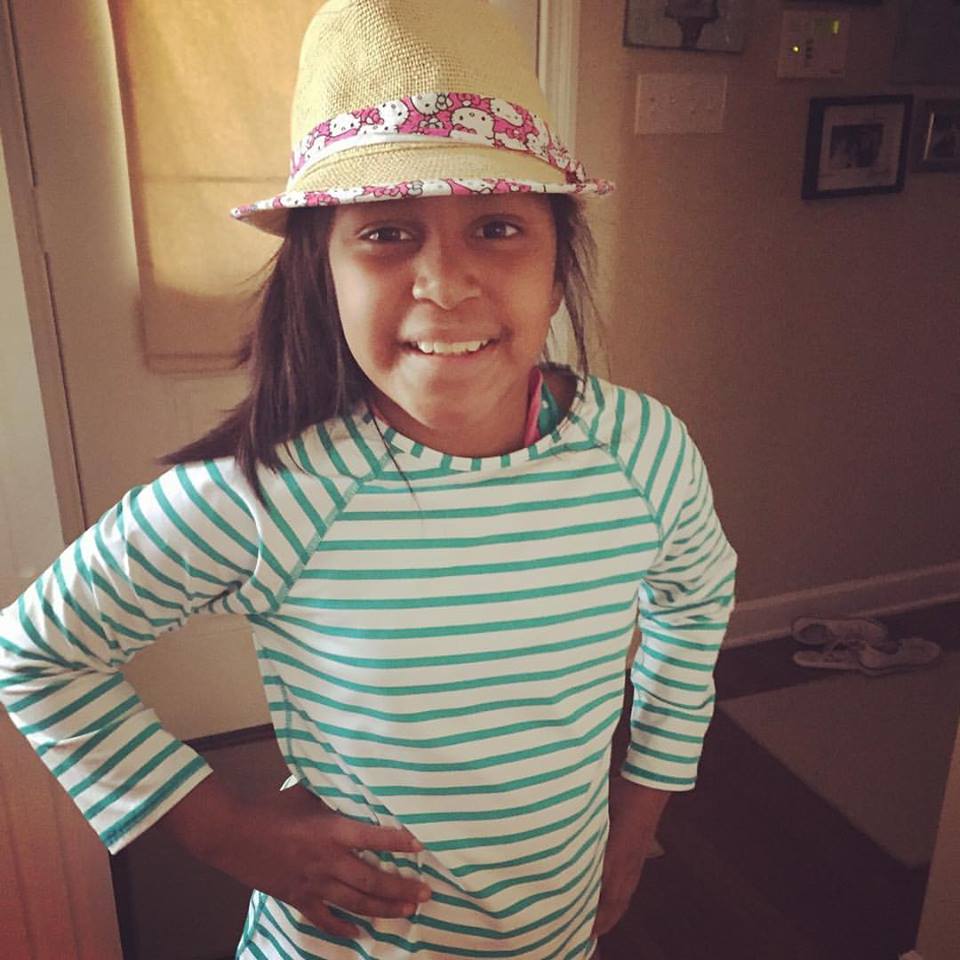

Much to the Burney’s joy, however, they were able to come home with Demi, their healthy baby girl. Michelle and Barry are grateful every day and they recognize the unselfish love of her birth mother to give up her child, with faith that her child would have a better life in the United States than she could in her native Guatemala, where 50 percent of all families live in poverty, half of all children have stunted growth, and the childhood mortality rate is five times higher than that of the United States. Michelle and Barry are keenly aware that having Demi as their child is miracle of God. Just one month after Demi was adopted, adoptions were officially shut down in Guatemala, where they continue to be shut down today.

“All I can say is that it’s such a God thing that we are able to have our Demi, who looks different on the outside; but likes to dance, eat sweets, and claim boys have cooties—just like every other Southern girl.”

Demi never forgets to pray for her native land and its people, so they may find relief to from poverty one day. She hopes to meet her birth mother and wants to learn more about the Guatemalan people.

“Through this whole process, I’ve learned to be patient with myself and life in general, and I’ve developed a greater passion for people, particularly for minorities of different countries. I see their struggles, and I know that my child will experience some of the same struggles. I see their achievements, and I celebrate the opportunities that Demi has in this country.”

When Michelle went through the adoption process, she was an academic counselor on the Holmes Grenada Campus, so the Holmes family has been a part of Demi’s story from the beginning of her life in the United States. Michelle and Barry appreciate the support they felt from Holmes throughout the challenging and, sometimes discouraging, adoption process and they hope that their story and their family’s journey through the process of adoption is an encouragement for others not to give up on their dreams in spite of obstacles they may encounter along the way.